August 16, 2021

The Actors’ Equity Association was founded 108 years ago in 1913. It is a trade union that today represents over 51,000 professional actors and stage managers in the United States. Equity promotes theatre to society in general while safeguarding the professional well-being of its members. It negotiates wages and working conditions, and provides other benefits, such as pension plans and health insurance. Equity is a powerful and positive influence on our industry.

Equity has a common condition included in the contracts for its members. It is generally known as the “ten out of twelve.” This condition sets an allowance of a twelve-hour work day, so long as no more than ten of those hours are active working hours, under certain conditions. Below is one example.

On a non-performance day during the seven-day period prior to the first paid public performance of a production, the Theatre may schedule two days of “10 out of 12” consecutive hours for each production.

Collective Bargaining Agreements. League of Resident Theatres, 2017.

(b) There shall be no more than two days of rehearsal of “10 out of 12” consecutive hours in any workweek. In non-Repertory companies, no “10 out of 12” day as referred to above shall be permitted unless there has been at least a 20-day interval from the previous production’s last “10 out of 12” day. No “10 out of 12” day may be followed by two consecutive two-performance days.

The ten-out-of-twelve is not what it was intended to be.

Leading up to the opening or preview of a production, it is typical to begin technical rehearsals (or “tech”) with one or two “ten out of twelves” and a six-day work week. This means one or two days in which everyone involved in the production is required to be present for twelve hours of the day, with two of those hours designated as breaks during which times they are allowed to leave the premises. This condition provides what has traditionally been considered to be adequate for the well-being of the performers and artistic preparation of the show.

This mandate has persisted throughout the current living memory of the theatre industry in the United States. The ten-out-of-twelve is a staple concept for putting up a show.

The mandate was created to protect the well-being of actors. In the hurried world of the theatre industry, it has created an expectation that most likely was not intended. Actors are called for ten-out-of-twelve hours and are expected to be dismissed promptly when that time is complete. Around this, the designers, technicians, director, stage management, and other contributors are typically ready and waiting to ensure that those ten hours of time with actors are used to their fullest.

“Everyone looks at the time frame and it seems like the artistic part goes out the door. We’ve got to fit all of this in, we have this time limit, and we just have to do it. And everyone’s working from that mindset” The one thing that I notice all through my years is that as soon as everyone says ‘okay tech is going to start tomorrow,’ everyone has already gone into that stress mode. We haven’t even gone into the room on the first day but everyone is prepared for that stress mode of being in that room for those long, long hours. And then you’ve got the tiredness. Everyone is trying to put their all into it. Because we are professionals. If you give us a task, we’re going to do it. Nobody wants to fail.

Lisa Dawn, production supervisor for Disney’s Frozen nationally and internationally.

“For the majority of people, it’s fourteen out of sixteen – if you’re lucky.”

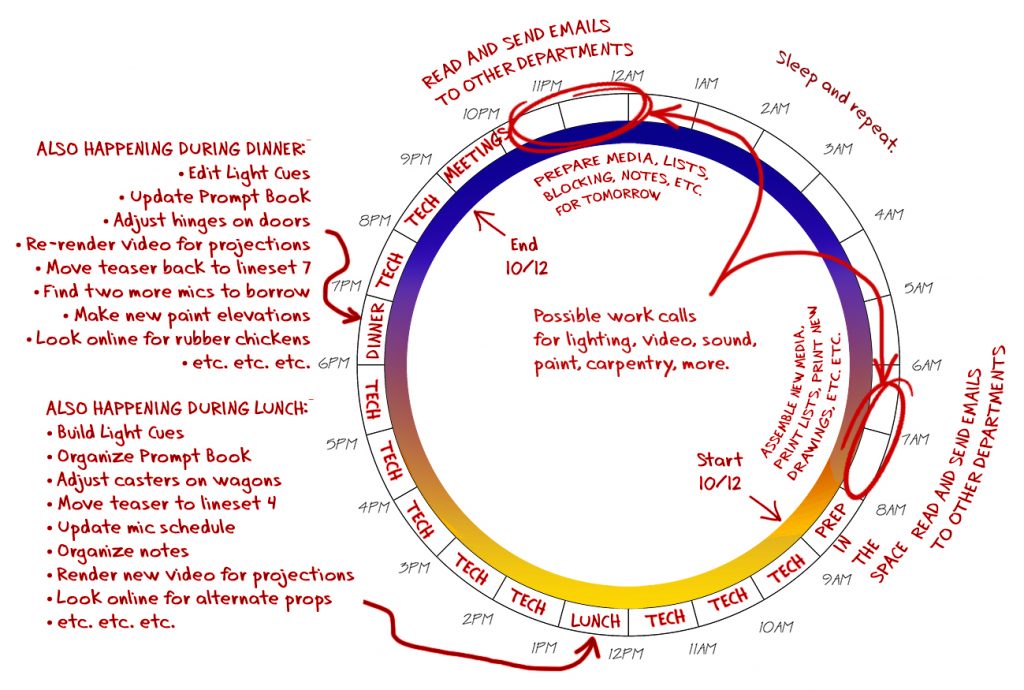

We have built an expectation throughout our industry that we will begin a ten-out-of-twelve technical rehearsal at, say, 9AM. We might break for one hour at lunch, and for one hour at dinner. At 9PM, the actors will be dismissed for the day. To make this happen, many people who are not actors need to be working well before 9AM, during those two meal breaks, and well beyond 9PM.

There is preparation to be done in the morning. There is – always – heavy discussion being done and adjustments being made during meal breaks. There are meetings that can last for hours at the end of the day, after the twelve hours is theoretically ended. Designers and their teams inevitably work hours and hours between these rehearsals to be ready for the next tech. Directors are communicating with all departments steadily. There are emails, emails, emails to read and to send regarding the show. Beyond all of this, the stage management team is the first in, the last out, and must orchestrate and update all schedules to keep all of this running, constantly.

“I just have to start out: It’s a lie – in the name. ‘Ten out of twelve’ only names the Equity mandate … For the majority of people, it’s fourteen out of sixteen – if you’re lucky. And that doesn’t count the invisible labor of preparing for the day. It doesn’t count the emails and the setups at the end of the day. So ten out of twelve is actually allowing for the standard of what is a healthy tech week to be centered around the people who it impacts the least. That’s how we know it’s an oppressive structure. Because we’re saying ten out of twelve is doable because the actors are being called only ten hours when that’s already extensive and it makes completely invisible the majority of disciplines and departments that have to show up in order to make those ten hours work. And those ten hours only work with excessive emotional labor from the departments who are there fourteen out of sixteen. And let’s be honest: after that sixteenth hour, the amount of work just carries into the next day. So where are the brakes, really? So, one, it’s a lie. The name itself makes people invisible.

Rachel Spencer Hewitt, Founder of Parent-Artist Advocacy League, actor for Broadway, regional theatre, and film.

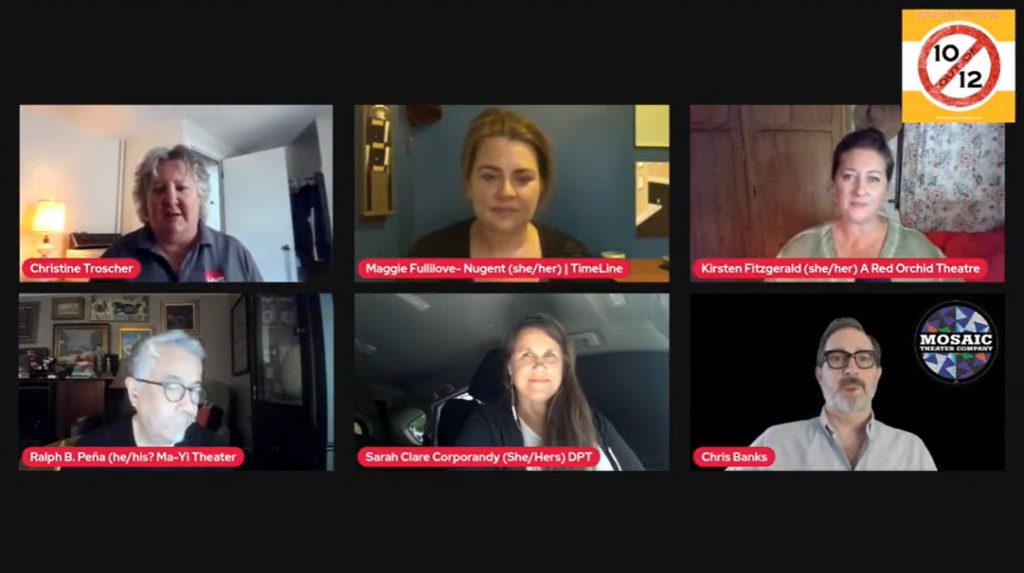

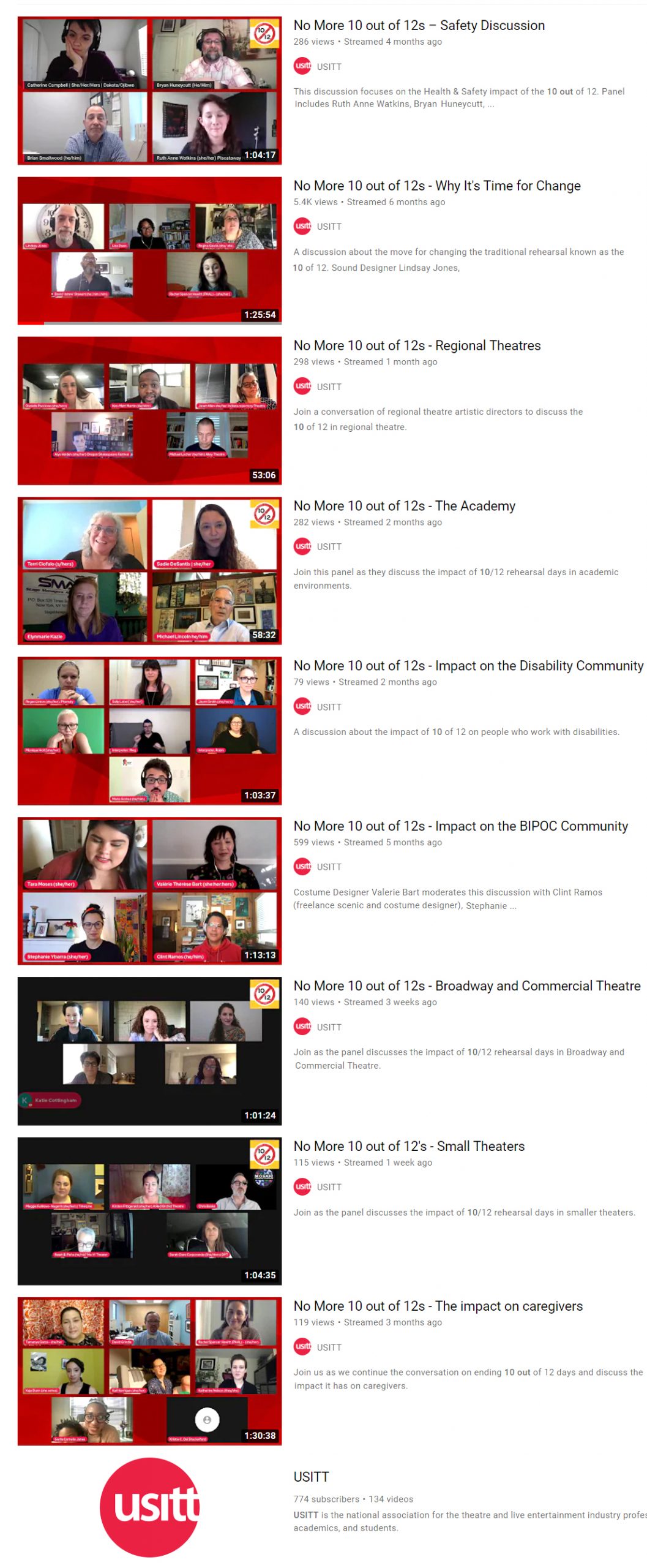

The United States Institute for Theatre Technology (USITT) has been live-streaming a series of discussions with the designation “No More Ten Out of Twelves.” These have included representatives from every layer and aspect of the live theatre industry.

In her opening remarks speaking in a USITT forum, Rachel Spencer Hewitt made striking points in a three-point list. It is unfair and cruel to call a rehearsal a ten-out-of-twelve if the majority of people must work far longer than that in order to make it happen.

The model has been questioned and criticized in the past, but COVID 19 was an historical event. The entire industry stopped dead, all at once. The pause granted the industry time to reflect on people, on quality of life, and on ethics.

Classicism and Elitism

“Number two: it does not take into account the intersectionality of this labor; the finances; the classicism between being able to work ten out of twelve hours for one-to-four days when we talk about parents and caregivers. The childcare amount of money that goes into it. And we’re talking from a privileged standpoint. The last contract I worked was a wonderful regional contract; well-paid. By the Thursday of that contract I had nine dollars in my account, and I was working a full-time job during that show. I had come from a privilege standpoint so the idea of job opportunity and the intersectionality of how race and gender impacts employment and how you’re able to sustain the financial pay and the roles that you get, the positions that you get – it’s a classist structure because it only allows those who are privileged to semi-succeed.

Rachel Spencer Hewitt, continuing in the same streaming USITT forum: “No More 10 Out of 12’s- Why It’s Time for Change.”

In the industry we have heard it many times, “Well, that’s just how the theatre is.” We all learned to work under these conditions when we began – many as teens in high school. The model was cemented for us in college. Those of us who teach have perpetuated it. It is the air we have been breathing for generations.

In order to participate, you must have advantages in place. You might be young, single, without ties or commitments. You might have a partner or a spouse who can keep your home-life running. You might have family who you know you can fall back on if things get rough. You might simply have background money in the bank that you can use to keep you going. If you have dependents who require a little regularity, you will have trouble.

“We’re filtering people out before they even get into the field.”

“With these working conditions, we’re filtering people out before they even get into the field. We’re not as equitable as we could be, simply because of these working conditions.”

Lindsay Jones, Tony nominated composer and sound designer and co-founder of the collaborator party

The structure does not welcome people who have or want children, pets, elderly parents, a stable household, and for many, mental health. It is easiest to function in the theatre if one can afford financial risk, afford childcare, and can afford to ignore everything but the work. It is easiest to do this from a place of privilege. This privilege is more commonly found among white Americans than others. Statistically, white American communities have had far greater opportunity to build up wealth, support structures, and stability within their families. Working conditions that favor such privilege are hostile to BIPOC communities and families. This raises obvious ethical issues. It also raises artistic issues. What is our purpose if we are stifling voices or silencing stories?

“Principles for Building Anti-Racist Theatre Systems”

“The impetus for this discussion was the We See You Demands:

Chris Banks: Production Manager at Mosaic Theater Company of DC

‘We demand healthcare without dependence on work weeks, or a lower threshold for BIPOC artists hired less often. We demand shorter, more humane tech days and work weeks with more time allotted for the production process.‘

It’s about giving artists agency over their experience and their own life.”

“We See You, White American Theater” (WSYWAT) is an alliance of arts workers. All are people of color. They began a movement in 2020 on June 8 against racism in the American theater. The movement is centered on a twenty-nine page document titled Principles for Building Anti-Racist Theatre Systems. The document clearly states demands for changes in the industry. These include adjustments to language, creative team compositions, hiring practices, artistic practices, and much more. The language that addresses working conditions has been catalytic to the conversation on rehearsals and tech.

“For myself and for many people who read that document and the list of demands that ‘We See You White American Theatre” put out, It was like a splash of cold water in the face. It was a huge wakeup call. I think we are having this amazing moment in time where this pause is giving us the ability to completely reevaluate everything about our working environment and how we treat one another; things we had just previously seen as just, ‘well, that’s how it is.’ We have the opportunity to question all of those things and to really sort of think about what we want our work environment to be in the future and how we want to be treated in the future … This is a roadmap for change and we need to start working on it.”

Lindsay Jones, Tony nominated composer and sound designer and co-founder of the collaborator party

“People thought ending child labor was going to be too costly too. Sometimes you just choose to do better despite the cost.”

Kristin Dwyer, responding in the comments during “No More 10 Out of 12’s- Why It’s Time for Change.”

The “We See You W.A.T.” movement is separate from the “No More 10 out of 12s” movement, but they share many goals. WSYWAT catalyzes the 10/12 movement by providing a higher ethical need. Too often, theatre culture glorifies self-sacrifice. We take pride in our willingness to give things up for our art. It is not a healthy culture, nor is it constructive. The “We See You” movement provides a slap in the face to American theatre culture: if you won’t make these changes for yourself, then do it for the BIPOC community.

Use of People and Time

“And the third thing I would say is that it doesn’t work. It doesn’t. I’m a hard worker. I’m great at tech. I have so much fun with my friends … It’s not the collaboration that I want to get rid of. It’s the idea that even the Harvard Business Review supports: longer hours does not mean more productive hours. It actually just means that we’re exhausting ourselves before we present to an audience, which to me is the most counter-intuitive understanding of how to prepare a show.”

Rachel Spencer Hewitt, continuing still in the USITT forum: “No More 10 Out of 12’s- Why It’s Time for Change.”

The rule for the ten-out-of-twelve is hurry up and wait. Everyone must be at places at the start. We step through each moment and work out the requirements to make it happen. There is a huge advantage to having the entire company present. For every moment, everyone is available for communication and integration. We always have the people we need available to solve the problem and move ahead. The drawback is that many actors and technicians might sit around for hours doing nothing at all.

“10 out of 12s are what we did in school. Those are allowed in contracts. Therefore it must be the right way.”

Kirsten Fitzgerald, Artistic Director for A Red Orchid Theatre in Chicago.

We waste a lot of people’s time, though we have learned not to think of it that way. We try to speed up the process with more preparation. Each department puts in hours late at night and in the early morning to streamline the next day’s efforts. The method we use has merits. It is a very useful tool. We might spend way too much time working in that mode.

What 24 hours during tech might look like:

“I have a friend who told me the other day, ‘The next day when I show up for work I spend the first couple of hours undoing the work that I did the last couple of hours the night before in that ten out of twelve because I was not [mentally] there.'”

Regina Garcia, Chicago-based scenic designer, head of the Scenic Design program at The Theatre School, DePaul University.

Proposing New Models

“We are trying to find a different way to make the sandwich.”

Maggie Fullilove-Nugent, Production Manager for Timeline Theatre Company in Chicago

It can be hard to imagine how to do what we do in a different manner. Sometimes weather or other circumstances forces the schedule to change radically. A snowstorm might completely eliminate an entire ten-out-of-twelve rehearsal. When that happens, we find creative ways to stay on track even when an entire ten-out-of-twelve has been cancelled. The model has already been broken very successfully.

Some examples are already in place

Some theatres begin with a “dry-tech,” which is a technical rehearsal without actors. When the actors are added, it is common to adjust light levels, audio levels, and other things to account for what is discovered when actors are added.

Dry tech goes more quickly and easily than full-company tech. It brings lower stress, too. There are fewer people for stage management to manage. The designers do not feel the weight of so many people waiting on their choices. There is less communication happening, and scheduling is simpler.

Staff might convene with limited crew to work in the space AFTER normal tech has been partially completed. When part of the show has already had tech with the full company, the choices made by the creatives are wiser than at the original dry-tech. We know how bright that special needed to be in scene 1. We know what that audio level needed to be with that actor shouting and then whispering. After only a little bit of live tech, we are smarter than we were at dry tech.

“Larger Institutions are going to need help from the smaller institutions to show them how to do it because if you’re a rowboat in the sea its much quicker to turn around than a cruise ship”

Sarah Clare Corporandy, Producing Artistic Director with Detroit Public Theatre, Managing Director for Chautauqua Theater Company.

One new model might be to tech only parts of the show with the full company. Pick a selection of both simple and complex scenes. Take the time to get these working well. Then return to a dry-tech model. Send the actors home, and let the designers and technicians hammer out the rest based on what they have learned. Then bring everyone back for a full run-through knowing that it will be a start-and-stop.

Implementing a new model for tech will be clumsy the first time. It will be necessary to keep the parameters defined. We must limit working hours both inside and outside of the space. We must map out new routes to performance that make smart and efficient use of everyone’s time. Finally, we must create an industry that is kind to us, and we must stop taking pride in suffering.

Other tweaks and solutions

Production meetings at the end of the day might be replaced with a structured electronic conversation. This could be a standardized email exchange, or a new app that allows good communication after tech without keeping people late.

There is some taboo associated with video-recordings of shows, and that spills into the rehearsal process. If we normalized working from a video-recording of the show, many lighting cues could be built without the actors present.

Every show has its own unique needs. We should create a toolbox aimed at getting work done with fewer people and shorter calls. We should have a wider variety of tech-rehearsal models available as partial-day components. Depending on the needs of the show, we could build a tech schedule that satisfies the needs of any show and maintain commitments to quality of life and kindness.

“People always think that ten out of twelve is the cheapest way to do something. They believe that this has become the most economical way to produce theatre is to jam all of these things into these long rehearsals … What we’re finding is that if you work for more than eight hours a day, you are less productive. As a result, as those hours go on, the hours you’re continuing to pay, you’re seeing less return in terms of what labor is possible. If you do those days multiple days in a row, now you’re actually affecting the productivity of all of the days … As time moves on, you’re less able to make a return on your investment. … When I talk to theatre producers and they say ‘I can’t afford to make this change,’ I can say to them, point blank, ‘You’re already wasting your money. You’re not spending your money as efficiently as you could be.'”

Lindsay Jones, Tony nominated composer and sound designer and co-founder of the collaborator party

“It’s this process that we have spent decades, centuries developing in theatre, of how much time it takes to make the thing. In my experience, the process will expand to fill as much time as you give it. So we’ve put ourselves in a place where we say, it’s going to take this many weeks to rehearse and this many hours to tech, and we take that as gospel now.”

Evan O’Brient, New York Theatre Workshop’s producing manager. AMERICAN THEATRE, Theatre Communications Group, 20 Aug. 2020.

Sources:

- “No More 10 Out of 12’s- Why It’s Time for Change,” uploaded by USITT, streamed live on Jan 27, 2021, https://youtu.be/vxgu-oVM-z8.

- “No More 10 out of 12’s – Small Theaters.” uploaded by USITT, streamed live on Jul 28, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3fCz-F13HY.

- “Collective Bargaining Agreements.” League of Resident Theatres, 2017, lort.org/agreements. http://lort.org/assets/documents/2017-22-LORT-AEA-Agreement-Unsigned.pdf.

- “Holy Post – Race in America.” Phil Vischer, Jun 14, 2020. https://youtu.be/AGUwcs9qJXY.

- Pierce, Jerald Raymond. “Time for a Change: What If We Cut the Long Hours?” AMERICAN THEATRE, Theatre Communications Group, 20 Aug. 2020, www.americantheatre.org/2020/08/20/time-for-a-change-what-if-we-cut-the-long-hours/.

- “No More 10 out of 12s – Regional Theatres,” uploaded by USITT, streamed live on Jun 16, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmVRlHNhumE

- “We See You W.A.T.” Principles for Building Anti-Racist Theatre Systems, June 8, 2020, www.weseeyouwat.com/.

Author

Matt Kizer lives with his wife and son in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He is the Director of Theatre for Plymouth State University, where he has been the head of the design and technology program since 1996. He specializes in projections and HTML tools for theatre and theatre education.

He has designed scenery, lighting, and projections for national tours, theatres, and universities in the United States and internationally. His work has been staged as part of the Prague Quadrennial, The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.; in Potsdam, Germany; in the United Kingdom; and in venues across North America.

He has presented workshops for many universities and institutions, including the Cyprus Centre of Scenographers, Theatre Architects and Technicians (CYCSTAT) in Nicosia and the National Opera Association in New York City. He served as faculty lighting designer for Operafestival Di Roma in Rome, Italy with the Orchestra Sinfonica dell’ International Chamber Ensemble at Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza. He serves as webmaster and contributor for BroadwayScene.com, AllTicketsInc.com, BroadwayIQ.com, and BroadwayEducators.com, all New York-based websites for theatre resources and Broadway sales.

He maintains a large library of educational theatre tools for online learning including various virtual lighting labs, directing studios, improvisational acting tools, and more.

He holds a BA in Theatre from Purdue University, and an MFA in Design from The Ohio State University.