In April of 2018, members of several groups collaborated at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire in the United States. They engaged in a workshop production of A Dream Play, by Swedish playwright August Strindberg. Jump to video

Some of the creative team had been brought together originally through The International Organization of Scenographers, Theatre Architects and Technicians, or OISTAT. OISTAT is a network of over thirty centers, including the United States and Cyprus.

A Dream Play was first produced in 1907. It is heavily expressionistic with elements of surrealism and symbolism. The play centers on Agnes, the daughter of the Vedic god Indra, who descends to Earth to learn about life as it is experienced by human beings. Humans are presented as being beset with harsh choices. Futility, frustration, and dilemmas define much of the action.

The play is beautiful in that it contains no judgement, and no blame. Agnes experiences only compassion and empathy for humanity. She experiences the events of the play as if she is dreaming. At the end, she awakens and returns to the gods. The telling of the story becomes the only priority. For the artists involved, there are enormous opportunities for choices. In this dream, anything can happen.

This was a workshop production. Typically, professional courtesy requires that we restrain ourselves from giving much input on work that is other people’s prerogative. Set designers discuss scenery. Lighting designers discuss lighting. For this process, creative input was encouraged from everyone in the company.

Normally, we try to lock down design and movement choices by the time we begin technical rehearsals. This time, we allowed ourselves to continue making changes almost until we opened. Decision making was flexible. Coming from different cultures, the expectations of how each would contribute were ambiguous.

The venue was a combination black-box/thrust theatre. The set was my design. It was a deliberately flexible design that allowed for rapid visual changes. I included a stock, white-tile-floor as a visual foundation that would would respond well to the heavy use of lighting and projections that were anticipated.

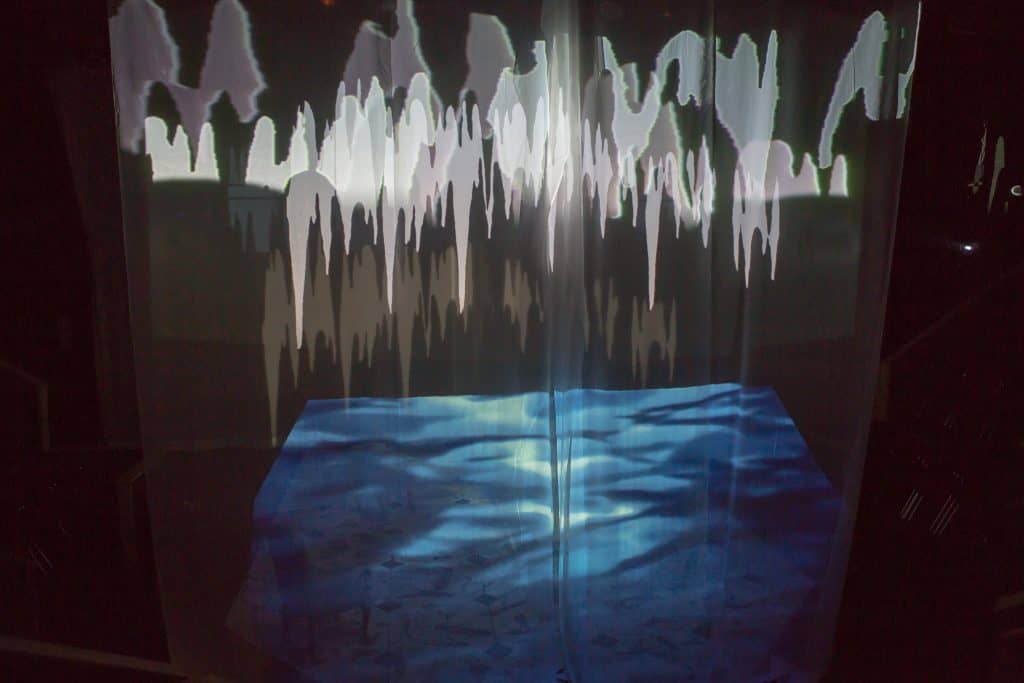

Sheer fabric drapes could be dropped in various locations in the space, acting as scrims and as projection screens. Slides, fire poles, and ladders allowed abrupt, but playful movement between the upper and lower levels.

Projections were focused all around the space, on the scrims, and on the floor. No decisions were made ahead of time as to how any of this would be used by the director or by the actors.

The play was directed by Dr. Paul Mroczka. He worked with the actors to establish a baseline for character and movement. A lot of room was left for input during a two-week period before the first performance.

The lighting was designed by Giorgos Koukomas, a Cypriot with the Cyprus Theatre Organization (CTO) in Nicosia. Koukoumas designs for spaces affiliated with the CTO. He also designs for some of the ancient amphitheaters in the western Mediterranean. There are similarities between amphitheaters like those, and the venue in which A Dream Play was being staged. New aspects of lighting design theory were introduced to the students at Plymouth State rooted in the use of the floor as a backdrop.

Costumes were designed by Danee Grillo. The production included a complete musical composition and sound design by Christopher Komiserak, a Plymouth State student.

The students got to participate in a creative process that broke with what is taught as the standard in the United States. The relationship between the director and the designers was left open almost to the end of the process. We often drill our students in the “right way” to do things, according to the rules and the hierarchy. This makes for a very efficient machine that can mount large shows effectively; but it can also get in the way of innovation. This literature was ideal for these circumstances. A production model was employed that allowed departure from habit. Any idea was welcome even very late in the process.

When we collaborate across cultures, nations, and languages, we force ourselves to stop and decide how we want to work together. We stop running on autopilot. We expand our understanding of what we are doing. We further our art. This is one of the most important reason to seek out collaborators across international lines. When we walk out of our comfort zone, we encounter new ideas. We adapt, and we grow.

Below is the original video version of this article. Check your audio.